MGNREGA: All one need to know, as published by IDR - India Development Review

MGNREGA: All you need to know

Does MGNREGA still have an impact? Learn about the scheme's funding, state-wise performance, role during the pandemic, and benefits to women and migrant workers.

The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) was passed by the Parliament of India in 2005 and came into effect on February 2, 2006, as a social and legal measure that guarantees the ‘right to work’. Renamed Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) in 2009, it guarantees at least 100 days of wage employment in each financial year to every household that is willing to do unskilled manual labour. The act has its roots in the Maharashtra Employment Guarantee Scheme (MEGS), 1972, which was the first to recognise the right to work, and the success of which paved the way for MGNREGA.

MGNREGA is a demand-driven programme, conceptualised to create and enhance livelihood security for the most vulnerable households in India. Keeping the citizen at its centre, planning takes place at all levels of the government administration starting from the bottom.

How does MNREGA work?

Panchayati Raj institutions (PRIs) play a vital role in planning and implementing the act’s provisions, signifying the importance of decentralisation and decision-making at the grassroots. The nature and choice of work is decided in consultation with the citizens in open gram sabha assemblies, and ratified by gram panchayats. To ensure accountability and transparency, it is mandatory for state governments to conduct social audits to review the utilisation of funds.

Allocation of work is done directly through the government without any stakeholders in the middle, and preference is given to unskilled workers—who must be employed within a five-kilometre radius of the village. The act permits more than 260 projects classified under four main categories: public works relating to natural resources management, individual assets for vulnerable sections, common infrastructure for Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana-National Rural Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NRLM)–compliant self-help groups, and rural infrastructure.

The gram panchayat is the main facilitator for households that wish to apply for work under MGNREGA. The first step that an unregistered household must take is to apply for a job card through their gram panchayat. Once they are issued a job card post verification of their documents and confirmation of their eligibility, they have to submit an application for employment. It is the gram panchayat’s responsibility to allocate work within 15 days of the request and provide wages within 15 days of job completion.

Who funds MGNREGA?

The central government provides 100 percent funding for wages for the unskilled manual work, and covers 75 percent of the material cost. Twenty-five percent of the material cost is borne by state governments.

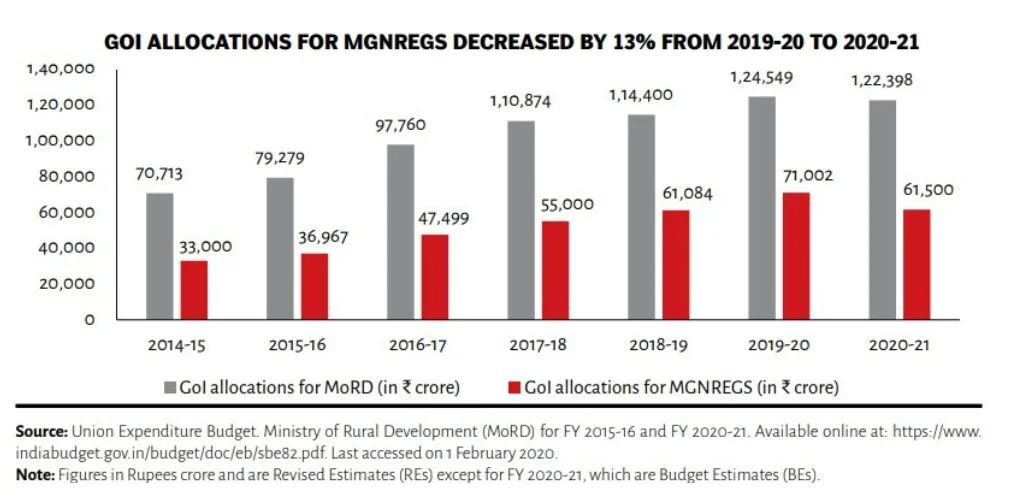

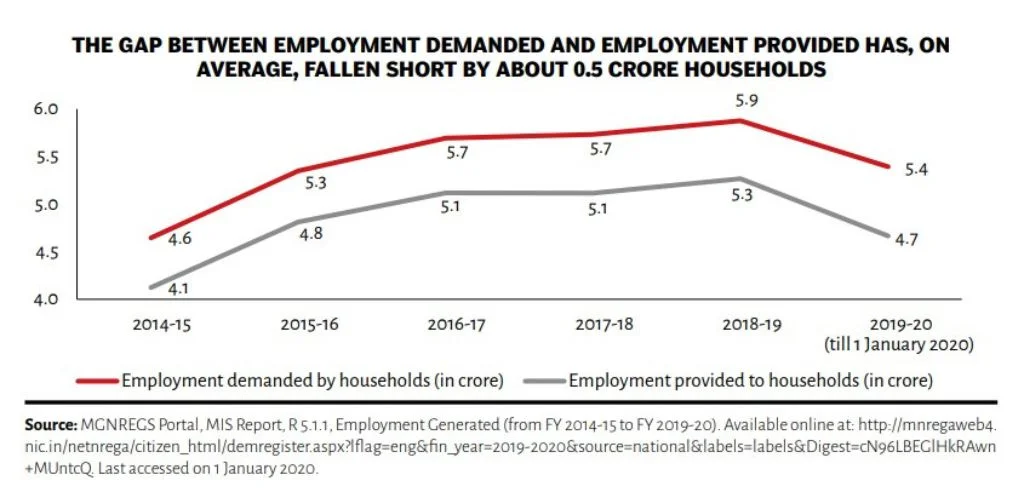

The availability of funds for MGNREGA has been inconsistent. While the funds rose by approximately 25 percent between FY 2008–09 and FY 2009–10, they fell sharply after FY 2011–12. Funds rose consistently from FY 2014–15 to FY 2019–20, but fell again in FY 2020–21. Over the years, the amount of pending liabilities (accumulated payments) due or expenditure incurred by the states over and above available funds has been increasing. These liabilities have accumulated as a result of delays in payments for both wages and material costs and are to be reimbursed by the central government. Funds available under MGNREGS have failed to keep up with expenditures incurred and are constantly exhausted before the end of the fiscal year. New projects to be implemented are also continually added even as previous projects are left unfinished. This leads to inefficient utilisation of funds.

View a detailed statistical analysis of the MGNREGA budget for FY 2020–21 and 2021–22 here. Read about how issues with government payment systems cause delays.

How did MGNREGA fare during the pandemic?

The onset of COVID-19 was a major challenge for unskilled workers. There are approximately 139 million internal migrant workers in India, and most of them are daily-wage labourers. The struggle to earn a daily wage to make ends meet, unorganised employment, and lack of financial security are just some of the issues that plague India’s internal migrants. These issues were further exacerbated during the pandemic as the lockdown brought manufacturing to a standstill. This triggered a mass exodus of workers who returned to their villages due to lack of work.

Recognising MGNREGS’s potential as a source of employment during this crisis, the Government of India, under its Atmanirbhar Bharat stimulus package, allotted an additional INR 40,000 crore to the programme. This brought the total budget to INR 1 lakh crore—0. 48 percent of India’s GDP—for FY 2020–21. Further, the average wage rate was raised from INR 182 to INR 202 per day. World Bank economists however recommend a funding allocation akin to 1.7 percent of the GDP during normal times.

A study by Azim Premji University finds that during 2020–21, approximately 39 percent of all job card–holding households interested in working under MGNREGA did not get a single day of work. For households that found work in both the periods (pre COVID-19 and during COVID-19), increased earnings from MGNREGA compensated for somewhere between 20 and 80 percent of income loss. So, MGNREGA managed to make a marked difference, protecting the most vulnerable households from significant loss of income.

Read more about migrant workers’ access to MGNREGS during the pandemic here. Read more about MGNREGA’s performance during COVID-19 here.

How do India’s states perform on MGNREGA?

MGNREGA is implemented across the country and there’s a marked variation in performance across states. Multiple research studies have been conducted to find a definite cause for such unevenness in outcomes but a satisfactory explanation has not been found. An important factor for generating high demand for work relates to the state’s efforts to inform and mobilise its citizens. A state with high capacity in terms of economic, organisational, and human resources has better opportunities to apprise its citizens of the scheme and have better implementation.

Even though the act guarantees 100 days of employment, the national average has always been below 50 days. Among large states, the highest average employment per registered person was provided in Chhattisgarh and Jammu and Kashmir in FY 2020–21 with 18 days of employment. This number is higher in smaller states in the Northeast, with Mizoram providing 86 days of employment per registered person in FY 2020–21, while Nagaland saw 24 days of average employment per person in the same year.

Chhattisgarh, at 14 percent, saw the highest percentage of families receive 100 days of work in FY 2020–21. Uttar Pradesh stood at 4 percent, while Bihar saw only 0.17 percent families find 100 days of work in FY 2020–21.

Rajasthan has been a top-performing state in terms of person-days generation and in 2022, rolled out an urban job guarantee scheme. With an increased focus on the need for employment generation since the pandemic, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Himachal Pradesh, and Jharkhand have also introduced urban wage employment programmes.

The highest daily wages for MGNREGA work are paid in the states of Haryana, Goa, and Kerala. Read more about MGNREGA’s performance in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh.

Do women benefit from MGNREGA?

According to the act, priority shall be given to women such that at least one-third of the beneficiaries are women who have registered and requested work.

The likelihood of women’s work participation is negatively impacted by migration, number of working males in the household, and highest education level, and positively by SC/ST social groups and number of children below 10 years.

Data shows that women consistently have a higher percentage of person days of work than men, with it consistently being more than 53 percent between 2015–16 and 2021–22. In some years this figure went up to 56 percent. Post COVID-19—in 2020–21 and 2021–22—the share of women fell to 54.54 percent, reflecting continued distress in the rural labour market.

Uttar Pradesh had the lowest rates of women’s participation in MGNREGA till 2017, but has been steadily increasing women’s participation and training women mates (worksite supervisors). In March, 2021, the Ministry of Rural Development announced the Mahila Mates programme under MGNREGA to better women’s participation as active stakeholders in the scheme, and not just have them labour on worksites. As per anecdotal evidence, women mates have also brought in more transparency. In 2020, Kerala (91.41 percent), Puducherry (87.04 percent) and Tamil Nadu (84.88 percent) were the top-ranking states offering women work under MGNREGS.

Read more about how MGNREGA works for women. Read about policy interventions that can support gender-inclusive employment.

Is MGNREGA still relevant?

There is no doubt that MGNREGA as a safety net has performed inconsistently. Some of the issues that have plagued the act since its inception are: low wage rates even after being adjusted for inflation, insufficient budget allocation, regular payment delays, penalisation of workers, de-capacitated banks, faulty data, inactive Aadhaars, and non-payment of unemployment allowance.

Despite severe criticisms since its inception, and mixed results in terms of implementation and impact, MGNREGA remains relevant as a safety net for the most vulnerable in India. Read a detailed analysis of the act’s relevance and how it can be improved to create greater impact here.

A Standing Committee on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj critically analysed the act in February, 2022, and suggested some solutions. It noted that the scheme should be revamped to meet the challenges in the wake of COVID-19, increasing the guaranteed days of work under the scheme from 100 days to 150 days with a uniform wage rate across states.

—

Comments